What Exactly Is Cosmic (Lovecraftian) Horror? A Cosmic Guide for Screenwriters

Cosmic horror is a horror subgenre that derives its fear from the dread of not only the unknown, but the unknowable. It’s driven by the inherent evil embedded in the universe. Unlike more traditional horror films, where the danger is governed by a predictable threat, cosmic horror tosses out the rule book altogether. It accesses the darkest corners of the universe where pure evil exists without explanation or reason. Recent examples of films in this genre include The Monkey, The Black Phone, Weapons and Sinners.

Human villains can be reasoned with, tracked, punished, or understood. Cosmic horror is scarier because it dismantles the very scaffolding we use to make danger legible: causality, motive, proportionality. The audience’s survival schema — fight, flee, bargain, overpower, destry, outsmart — becomes void. The result is a deeper, more visceral fear based on atmosphere rather than a jump scare. Some of these components also extend into certain sci-fi and fantasy stories.

Let’s dive deeper into the concepts that drive cosmic horror.

What Are The Key Elements Of Cosmic Horror?

Cosmic horror (Lovecraftian horror) emphasizes the universe’s indifference to humanity and the psychological, existential consequences of encountering realities beyond human comprehension.

Scale: Vast, overwhelming, and uncaring cosmic forces or entities far beyond human power.

Insignificance: Humans are tiny, inconsequential, and fragile within a universe that doesn’t care.

Unknown/ Unknowable: Truths or beings that can’t be fully understood; glimpses of them cause madness.

Cosmic dread over gore: Fear comes from implication and scale rather than explicit violence.

Atmosphere and slow-burn escalation: Unease accumulates; revelation is partial and fragmentary.

Unreliable perception: Memory loss, distorted evidence, conflicting accounts, or madness blur reality.

Human-centered horror offers an avenue of escape: act correctly and you might survive, or at least see justice served. Cosmic horror does not. It is randon and indifferent. It is devoid of morality and emotion. Its only end game is annihilation.

Good decisions do not necessarily yield safety, moral purity is not rewarded, and sacrifice can be meaningless. This produces a relentless anxiety that persists long after the film ends.

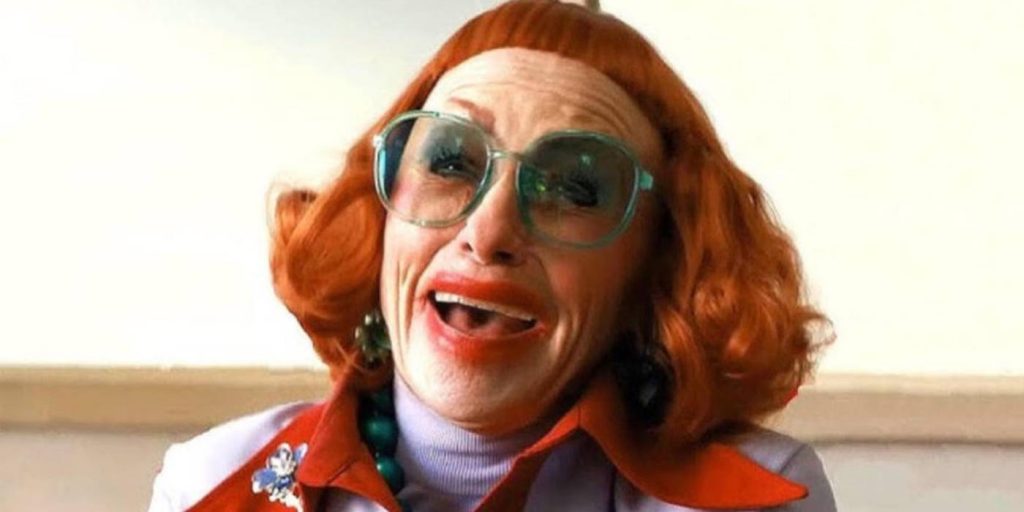

The Monkey. Photo courtesy of Neon / Everett Collection

Emotions Beyond Fear & Anxiety

Cosmic horror is not a single feeling, but a constellation of emotional and sensational responses. A lovecraft horror film will push viewers through a range of extreme emotions, sometimes contradictory, that deepen their experience.

Awe: The sublime sense of scale evokes awe as much as terror. Audiences feel small and powerless in the face of geological or cosmic vastness, and that smallness can be both beautiful and terrifying.

Nihilism and Despair: When meaning and order collapses, despair can follow — not just fear, but a bleak, heavy, inconsolable grief that is trivial against these cosmic processes.

Melancholy and Loss: Cosmic revelations assault long-held human assumptions. There is sadness for the world we thought we knew and for lost illusions of importance in the grand scheme of things.

Wonder and Curiosity: Even when knowledge harms, curiosity still propels characters and viewers forward. That ambivalence — being drawn toward dangerous truth — adds complexity, fascination and dread.

Loneliness and Alienation: The feeling that contact with cosmic realities isolates you from other humans is central to the genre. Survivors are often left incomprehensible and strange to those who remain in ignorance.

Paranoia and Suspicion: If the rules are unstable, everything becomes suspect. People begin to distrust memory, language, and each other, creating social dissonance as well as personal breakdown.

Existential Shame: Confronting an indifferent cosmos can generate shame — an acute awareness of human smallness and insignicance that feels moral even if it is not.

Weapons: Aunt Lilly (Amy Madigan) Photo courtesy of Universal Pictures

How Screenwriters Evoke Lovecraftian Spectral Emotions

Build Awe Before Threat: Start by expanding perspective gently: wide shots, historical artifacts, or myths that imply scale. Let the audience feel the sublime before you unsettle it.

Make Curiosity Compelling: Give characters credible reasons to probe the unknown. Their curiosity should feel human and believable so viewers mirror the impulse.

Undermine Slowly, But Surely: Don’t dump incomprehension all at once. Introduce anomalies and contradictions that escalate: small logical slips, then larger ruptures. The gradual erosion of certainty feels more traumatic than abrupt revelation.

Use Intimacy as Contrast: Anchor cosmic events in intimate human moments — family dinners, recorded messages, small kindnesses. When those anchors fail, the emotional fallout is harsher and longer lasting.

Let Sound Carry Meaning: Use sound to suggest scale beyond sight. Drones, subsonic rumbles, white noise and deathly silence can convey presence without identifying or showing it.

Keep Language Fuzzy: Allow characters — and the story —to skim around the truth. Dialog that stops short, reports that fragment, and language that loops back on itself convey cognitive strain.

Offer Emotional Rather Than Logical Resolution: Close a story on a felt truth — grief, acceptance, or defiant refusal — rather than an explanation. Emotional closure without ontological closure preserves the haunting aftermath.

Smoke/ Stack (Michael B. Jordan) Photo courtesy of Warner Bros.

Writing Cosmic Horror Stories

Start with a small, mundane detail and let it widen until the world feels weird and about to get worse.

A woman cooks breakfast; the radio mentions the tide, off by an hour. A child paints a sun without a face. A person keeps filling their glass of water even though it’s overflowing.

The oddities are easy to ignore at first — local gossip, a clairvoyant, a weekend news item — but they pile up as their significance escalates. Each new strangeness is a thin, plausible clue: maps with unlabeled places, a farmer’s field where crops lean toward something other than the sun, a child reading a book with blank pages, a clerk who answers questions nobody is asking. The narrator doesn’t explain; they observe and catalogue. There are no immediate indications of any danger; only a sense of other-wordliness and instability – sometimes absurdity.

Make your protagonist human and small in scale. Give them a regular life: a rent to pay, a sister who over worries, a failed ambition that still stings years later. Let their everyday commitments pull them toward the imminent hazard. Curiosity, duty, stubbornness — these are believable motives that lead people to pry at doors better left shut. When they find an object — a slate carved with geometry that expands the margins of vision, a recording with an incomprehensible undertone — treat it as a shard of truth, a piece in the puzzle. They read it, listen, translate; each partial understanding opens a window that can’t be closed.

Don’t show the dread; show the world’s reaction to it. Describe how the light changes in rooms that face north, a veiled old woman sitting on a chair, how clocks slow for ten minutes and then catch up, bodies in a state of suspended animation, how shadows linger after someone leaves. Let weather behave like a purposeful irritant: fog that fills alleys, rain that pauses over a dead lawn, but pours elsewhere. Use details that are precise and small so the reader trusts the scene even as reality is tested.

Use silence and uncomfortable space as characters. Long stretches with little action should twist the mood: an abandoned breakfast table left half-cleaned, an unanswered phone that rings in another room without being connected, a radio that hums with static between stations, a cemetery with exhumed graves.

When something does happen, make it an unsettling intrusion — a deep, low sound that the dogs refuse to identify, a landscape photograph in which the horizon tilts. Let events arrive elliptically: a neighbor disappears, and the notice on the community board is bureaucratically mundane, without elaboration.

Tap into the senses to unsettle and unnerve. Describe tactile anomalies (the person who keeps their hand on a live hotplate), olfactory misfits (smoke from an unknown source that makes you gasp), and auditory oddities (a distant choir of tones coming from a room only to find it is empty when entered).

Use distance and exaggeration rather than gore: the protagonist might glimpse a shape the size of a cathedral moving like a slow organism across a horizon, or feel the ground shift beneath a city block by inches. Fear should arise from realizing how small humans are inside processes that do not acknowledge them.

Let rules change without warning or explanation. Time can bend: an hour becomes a day in the memory of one character, a clock that always strikes at midnight, but misses one particular night, rooms rearrange themselves without human intervention. Science and reason provide fragments — but they never stitch together into a satisfying whole. The reader should sense lawlessness and randomness in the universe’s machinations.

Use point of view that blurs certainty and aggravate anxiety. An unreliable narrator whose notes are full of edits, struck-through lines, and insertions of dates that don’t align gives the story its own instability. Alternate accounts — a rescued diary, a researcher’s transcript, a municipal memo — can contradict each other. Present these fragments without building a case; let the reader assemble them and attempt to piece together a tangible explanation.

Build dread through escalation and restraint. Imply more than illustrate. Start with small losses — sleep, pets, crops — then make them more consequential: entire neighborhoods abandoned overnight, radio frequencies looping a single, untranslated syllable. Never offer a tidy solution (if any solution at all). If the protagonist thinks they understand a situation, let the understanding be partial and costly: a revelation that shrinks their moral universe or condemns a town to silence. Endings should leave residue.

Morality should be skewed and non-binary. Escape is possible, but laden with ignorance, or survival means returning to an altered world — a photograph with one face scratched out by hands that are not human or a neighbor that warns of impending doom.

Use motifs. Repeated images — a spiraling glyph scratched into doorframes, bells that toll at the wrong hour, the smell of salt after rain, grass that grows at lightning speed — gain penetrating menace through recurrence.

Finally, let human institutions fail or become corrupt. A university that hides vital research, a cult that calms itself with dogma, a municipal notice that reduces disappearances to commonplace statistics; these failures make the cosmic indifference impactful.

Write sentences that track the horror: simple ones for small domestic detail, longer, more tangled and omnipotent ones for moments when comprehension frays at the edges. End scenes on searing images rather than explanations or conclusions — a chair with a missing leg tipped over in an empty house, the slow withdrawal of tide leaving impossible footprints — so the reader carries the unease and uncertainty forward.

Cosmic horror stays with us because it touches a nerve: the desire to understand and control the universe and the dread that understanding might unroot us. It is scarier than human logic because it obliterates the scaffolding we use to feel safe. Finally, it generates a tranche of emotions— wonder, grief, isolation, shame — that standard horror cannot reach.

Join the Discussion!

Related Articles

Browse our Videos for Sale

[woocommerce_products_carousel_all_in_one template="compact.css" all_items="88" show_only="id" products="" ordering="random" categories="115" tags="" show_title="false" show_description="false" allow_shortcodes="false" show_price="false" show_category="false" show_tags="false" show_add_to_cart_button="false" show_more_button="false" show_more_items_button="false" show_featured_image="true" image_source="thumbnail" image_height="100" image_width="100" items_to_show_mobiles="3" items_to_show_tablets="6" items_to_show="6" slide_by="1" margin="0" loop="true" stop_on_hover="true" auto_play="true" auto_play_timeout="1200" auto_play_speed="1600" nav="false" nav_speed="800" dots="false" dots_speed="800" lazy_load="false" mouse_drag="true" mouse_wheel="true" touch_drag="true" easing="linear" auto_height="true"]

You must be logged in to post a comment Login