Why Horror Franchises Refuse to Die — And What Screenwriters Can Learn From The Good Ones

There’s something about horror that keeps audiences coming back. Despite the shuddering, jolting, and covering your eyes, no other film genre has so successfully generated sprawling universes, decade-spanning timelines, and iconic characters such as Michael Myers, Freddy Krueger, Ghostface who just won’t stay dead – for long. Whether it’s masked killers, demonic dolls, or death itself personified, horror thrives in repetition of its core characters and premises — so long as it continues to build and innovate itself.

With franchises like The Conjuring, Halloween, Saw, and Scream, one question lingers for screenwriters: what makes a horror franchise work?

The Rising Revenues: Horror’s Franchise Kings

Before diving into the how and why, let’s look at the box office numbers and Rotten Tomatoes review scores. These horror films are the heavy hitters which studios love adjusted to 2025 and based on global box office figures:

- The Conjuring Universe (including Annabelle and The Nun)— ~$2.25B | Tomatometer avg: ~60%

- Alien (including Prometheus) — ~$1.6B | Tomatometer avg: ~62%

- Halloween — ~$1.5B | Tomatometer avg: ~45%

- Resident Evil — ~$1.2B | Tomatometer avg: ~30%

- Saw — ~$1.0B | Tomatometer avg: ~25%

- It (Chapter One + Two) — ~$1.0B+ | Tomatometer avg: ~65%

Notable mentions that fall just below the $1.0 billion mark include Paranormal Activity and Friday the 13th ($900 million each), and Scream and A Quiet Place ($700 million each).

A notable aspect of these mind-boggling figures is that there isn’t often a direct correlation between box office and critical acclaim. Horror audiences are often more forgiving of middling (or mixed) reviews, so long as the film delivers on scares, spectacle, or mythology. They may not be so forgiving of negative reviews, but critical success can give franchises longevity, depth, and respect.

Where These Nightmares Began: The Inspirations Behind the Icons

Halloween: It All Started With a Shape in the Dark

John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) didn’t invent the slasher film, but it took it to a whole new level. A masked, silent killer. A babysitter alone. A suburban street that looked a little too much like our own. Michael Myers wasn’t just a killer — he was “the Shape,” an unknowable force of evil that transcended motive or logic.

Over thirteen installments, the Halloween franchise has undergone every transformation imaginable: cult conspiracies (The Curse of Michael Myers), campy crossovers (Halloween: Resurrection), gritty reboots (Rob Zombie’s Halloween, 2007), and most recently, a trilogy that re-centered trauma and survival (Halloween 2018–2022). Through it all, one thing remained constant: Michael returns, and Laurie Strode — portrayed with increasing depth by Jamie Lee Curtis — fights back.

The 2018 reboot was a turning point. It ignored all previous sequels and reset the original film’s emotional core. Laurie wasn’t just a survivor — she was a woman shaped, and scarred, by her past who refused to live in fear. That focus on psychological realism, wrapped in the familiar slasher mold, helped the film gross over $250 million worldwide – and rising.

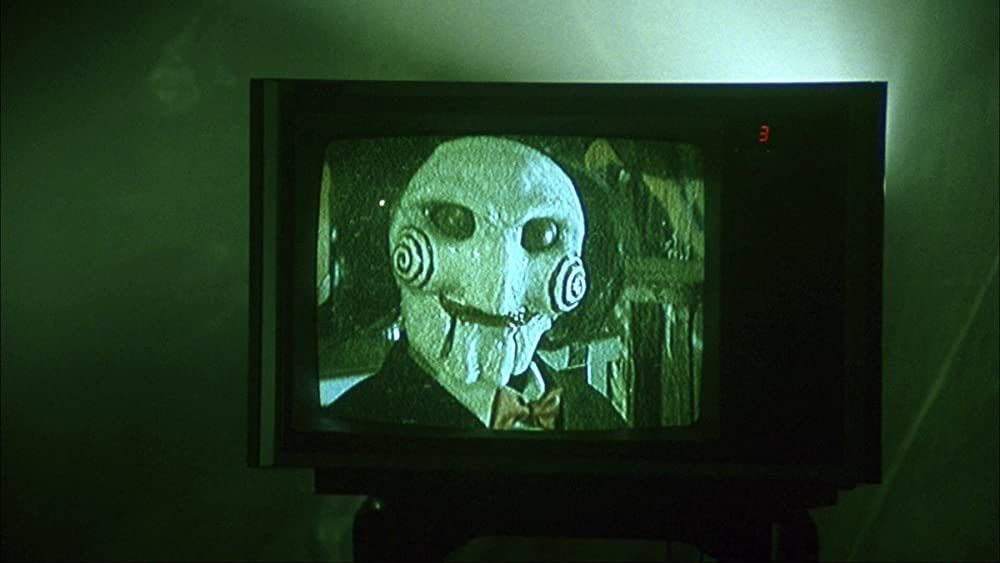

Jigsaw in Saw (2004)

Saw and the Psychology of Punishment

The genesis of Saw (2004) was as brutal as the franchise itself. Created by James Wan and Leigh Whannell, it was inspired by low-budget ingenuity and the existential question: what if someone punished others not out of vengeance, but ideology?

Jigsaw’s (Tobin Bell) traps were a direct response to a rise in grim, nihilistic horror in the early 2000s — post-9/11 anxiety made “torture porn” a commercial genre. But Saw stood out by giving its killer a twisted, but relatable, philosophy: he wanted his victims to appreciate life in the face of his being cut short bny disease.

Unlike most slashers, Jigsaw doesn’t kill — he offers his victims choices. That philosophical angle turned gore into a morality play, crafting increasingly elaborate traps and a worthy mythology. The franchise balances traps with themes of justice, redemption, and human weakness.

Over time, the timeline became labyrinthine, with prequels, apprentices, and secret reveals. Saw X (2023) breathed new life into the series by returning to basics: a focus on Jigsaw’s character and the emotional underpinnings of his “games.”

Scene from Final Destination (2000)

Final Destination and the Butterfly Effect

Final Destination (2000) started as a rejected X-Files spec script. The idea: what if death itself hunted you after you escaped your fate? Creator Jeffrey Reddick flipped the slasher formula by removing the killer entirely out of the equation — leaving an invisible, omnipresent force to portray the fateful killer.

The franchise’s Rube Goldberg-style death sequences became its calling card, as did the notion of “cheating death.” It wasn’t just about gore; it was about the paranoia of existing in a world where every random object or cruel twist of fate could be your undoing. A simple premise, endlessly expandable.

Lorraine Warren (Vera Farmiga) in The Conjuring (2013)

The Conjuring and the Real-Life Ghost Files

James Wan again struck box office gold with The Conjuring (2013), which drew on the supposedly true stories of Ed (Patrick Wilson) and Lorraine Warren (Vera Farmiga). Their real-life paranormal case files provided a well of lore, emotion, and franchise potential. What made it unique? The heroes weren’t victims — they were spiritual warriors determined to prove their beliefs.

While Halloween kept the slasher alive, another franchise quietly reshaped horror in the 2010s with a very different tone. When The Conjuring (2013) introduced Ed and Lorraine Warren — paranormal investigators based on real-life figures — it didn’t just launch a movie. It opened the door to a creepy universe.

Unlike most horror franchises that follow a linear path, The Conjuring Universe is sprawling: a haunted doll (Annabelle), a demonic nun (The Nun), cursed artifacts, exorcisms, and case files – all linked by the Warrens.

What makes this universe work isn’t just the scares. It’s the religious iconography, the moral stakes, and the spiritual consequences give each film a sense of thematic weight. Even skeptics can’t deny the emotional pull of a family fighting to protect their souls.

The universe has seen box office hits and misses — Annabelle (2014) stumbled out of the gate, while The Nun (2018) became a surprise box office juggernaut. But the success of this franchise illustrates a key principle: audiences respond not just to what haunts us, but why it haunts us.

Ghostface in Scream (1996)

Scream: Meta Horror and the Age of the “Requel”

Kevin Williamson’s Scream (1996), directed by horror legend Wes Craven, was born from both love and exhaustion. The genre had grown stale by the ’90s. Scream revitalized it by acknowledging that very staleness.

Inspired by real-life serial killer Danny Rolling and Williamson’s own obsession with slasher tropes, Scream blended horror with meta-commentary. Ghostface didn’t just stab — he quizzed his victims on horror trivia first. It was smart, scary, and incredibly self-aware.

In 1996, Scream sliced through a stagnant horror landscape by defiantly breaking all the rules — while telling you exactly what those rules were with a nod and a wink. It was clever, self-aware, but, crucially, still terrifying. Wes Craven and writer Kevin Williamson delivered a love letter to slasher films that also dissected them.

What kept Scream alive through six films (and counting) wasn’t just Ghostface’s mask or the inventive kills. It was the cultural commentary. Each installment acts as a time capsule, addressing the fears of its era: a snapshot of media exploitation, toxic fandom, internet virality, and legacy culture.

The original trio — Sidney Prescott (Neve Campbell), Gale Weathers (Courteney Cox), and Dewey Riley (David Arquette) — gave the series continuity and heart. Newer entries wisely shifted focus to a new generation while keeping the themes current. Scream VI (2023), set in New York, delivered the franchise’s highest box office returns ($166 million).

Katie Featherston and Micah Sloat in Paranormal Activity (2007)

Paranormal Activity and the Home Video Haunting

Oren Peli’s Paranormal Activity (2007) was a game-changer. Made for a reported $15,000 and filmed in his own house, it followed in the footsteps of The Blair Witch Project (1999) but hit the mainstream at a time when surveillance and “found footage” felt eerily real and popular.

The fear didn’t come from jump scares — it came from the dread of waiting for them. Every night, watching that static camera, wondering if the door would creak open. Its massive return on investment ($193 million globally) launched six more films and proved the power of slow-burn horror and minimalism.

Freddy Kreuger (Robert Englund) A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984)

A Nightmare On Elm Street: Freddy’s Playground

If Michael Myers is pure evil and the Warrens are spiritual warriors, Freddy Krueger is something else entirely: the haunter of the subconscious, a burn-scarred boogeyman who turned dreams into living nightmares.

A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) introduced a villain unlike any before. Freddy didn’t stalk you in the woods — he waited for you to fall asleep before he struck. This simple premise gave the franchise unlimited creative scope. Dream logic allowed for surreal set pieces, psychological depth, and blood-curdling kills.

Freddy, played almost exclusively by Robert Englund, became a cultural icon. But as the series progressed, it leaned heavily into humor, at times diluting the fear. By the time the 2010 remake arrived — with a darker, joyless Freddy played by Jackie Earle Haley— audiences rejected it outright. The original soul of the franchise was gone.

Still, the early entries like A Nightmare On Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (1987) show the value of character-driven ensemble horror, giving victims a sense of agency and power. It wasn’t just about survival — it was about reclaiming control.

Horror is About Fear, But Also Change

At their best, horror franchises don’t just exploit the fears and anxieties of the moment — they harness and mirror them. What scares us changes over time. In the ’80s, it was masked killers in the suburbs. In the 2000s, it was sadistic games and unseen entities. In the 2020s, it’s trauma, legacy, identity, and the internet’s influence on truth and fear.

Join the Discussion!

Related Articles

Browse our Videos for Sale

[woocommerce_products_carousel_all_in_one template="compact.css" all_items="88" show_only="id" products="" ordering="random" categories="115" tags="" show_title="false" show_description="false" allow_shortcodes="false" show_price="false" show_category="false" show_tags="false" show_add_to_cart_button="false" show_more_button="false" show_more_items_button="false" show_featured_image="true" image_source="thumbnail" image_height="100" image_width="100" items_to_show_mobiles="3" items_to_show_tablets="6" items_to_show="6" slide_by="1" margin="0" loop="true" stop_on_hover="true" auto_play="true" auto_play_timeout="1200" auto_play_speed="1600" nav="false" nav_speed="800" dots="false" dots_speed="800" lazy_load="false" mouse_drag="true" mouse_wheel="true" touch_drag="true" easing="linear" auto_height="true"]

You must be logged in to post a comment Login