- Do Characters Have To Be Likable? (Part 1)

- Do Characters Have To Be Likable (Part 2)

Not to spoil it for you, but the opening of The Shield is one of the most stunning in TV series history. The Vic Mackey character, leader of the ‘Strike Team’ that went after gangs and drug dealers does something unbelievable.

Mackey and his team raid a drug dealer’s house with a new member in tow. At one point, they secure the premises. Mackey turns to a new member of the team and shoots him in the head using a confiscated weapon.

Uh…what? Now this is Michael Chiklis so you’re pretty sure he’s the guy we’re going to be following in this show, but he just executed another cop. Without any apparent provocation. Maybe that cop was bent? No, that cop is actually the good cop. And as it turns out, he’s undercover with the mayor’s office because they ’re trying to take down what they believe is a corrupt team under Mackey ’s guidance and Mackey needs to eliminate him. Wow. How in the world did writer Shawn Ryan convince the producers that this was the way to introduce this character?

Challenging characters have existed in TV before, but they are not normally supposed to be the ones upholding the law. Tony Soprano springs to mind as a main character who we followed even though he was a murdering thug. But he really wasn’t a good guy – a ‘kiss the baby ’ character. Vic Mackey represented a sea change in main characters who opened the door for Dexter, Gregory House, Walter White, Jax Teller, and more.

But why do we embrace these challenging characters? And how do writers get us to follow them? There are plenty in history to choose from and this seems to be a natural extension of other anti-heroes who are not-to-be-admired characters.

Not Devils But Close

Even if television had little or no challenging characters before Tony Soprano and Vic Mackey, film did. And before film, novels and plays.

The bible features men and women who are less than upstanding. Samson was a philanderer and man of enormous sexual appetites who was used by God as a weapon to deliver the Israelites from the Philistines. Deborah, a prophet, likewise was terribly flawed but useful. The Good Book is filled with these types of characters.

Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini)

Shakespeare had MacBeth, Richard III, Iago – all characters who don’t fit into neat definitions of protagonist/antagonist or good/evil.

Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer was not a nice kid – he lied, cheated, and dragged others into his mischief including pretending he was dead and then showing up at his own funeral.

And yet, all these characters – and worse – are beloved and celebrated.

Let’s examine some strategies that help us write characters who are as nasty as gas station sushi.

The World

Perhaps the easiest way to make a character acceptable is to properly introduce their world. My Act I list includes a tick box for “The Normal World.” It’s a simple enough concept and essential to your story under any circumstances.

No one really expects Tony Soprano to be a nice guy. This is a given considering he’s a mobster. Mayhem, murder, thieving – these are the keys to existing in his world. No mobster can really escape the violence and brutality endemic in Tony ’s chosen profession. To do so would be to invite that violence to your door. You strike or you are struck; you kill or you are killed. Weakness will get you dumped off a pier with a set of concrete shoes.

In the 40s and 50s it was films like White Heat and Dillinger. Later, The Godfather and Scarface gave us central characters who live in violent worlds which helped to explain who they were and how they reacted to any situation. The Many Saints of Newark drills down into Tony Soprano’s youth to show us how he became the strong, vicious leader of the New Jersey mob.

Private detectives live right on the edge of these worlds of violence. Lew Archer, Phillip Marlowe, Jim Rockford, and others walk on the dark side of society so when they slap someone around or shoot a person we may not like it but we accept it given their existence and the situations in which they work. They have to be as hard as the people they deal with every day.

The young men in Attack The Block live in a housing project in London. The estate, as it’s called, is a place of violence and despair although not everyone in the juvie gang experiences this at the same levels. Moses, the leader, has no parents and lives with his uncle who is non-existent in his life. Without a strong parent figure, he’s walking a bad path. He robs and terrorizes indiscriminately when we first meet him. He does redeem himself at the end of the movie, but if the aliens hadn’t invaded, Moses was about to become one of Hi-Hatz’ newest drug dealers and would have been lost to society.

Moses (John Boyega)

Using a character’s world is a solid technique to explain how the characters became who they are and allows us to excuse their behavior in some measure.

Backgrounds

Dexter features perhaps the most challenging protagonist in recent memory. Here’s a psychopath, a serial killer who has been trained by his cop-father to channel his violent tendencies into destroying only bad people.

Accept the outrageous premise or not, it’s a neat way to make one of the least- redeemable characters in the world acceptable. Of course, vigilantes have existed before. Death Wish for example. But Dexter takes that concept to new levels because not only does the main character torture and mutilate his victims, he enjoys it. His slim justification rides a thin line between fascination and disgust. But given its amazing writing, acting, and eight interesting seasons, people embraced this character. And, there’s now also more coming from Showtime.

What shapes our characters explains them, mitigates them. This is why it’s so important to understand all the aspects of a character. If you don’t then your audience will not. How were they raised, what drove them to their current place in their lives. Even if it’s not wholly clear in the script, you need to know it. This allows you to make even the most unlikable characters, if not likable then at least interesting enough to want to follow.

Family

Tangential to the world and background is family. In the original The Sopranos we could forgive some of what Tony did based on his insane mother and uncle who plotted to kill him and take over the mob. Certainly, The Godfather showed us a deeply entrenched set of anti-social values that Michael Corleone rejected – or tried to reject – but in the end had to embrace to survive his father’s world of wise guys and assassinations.

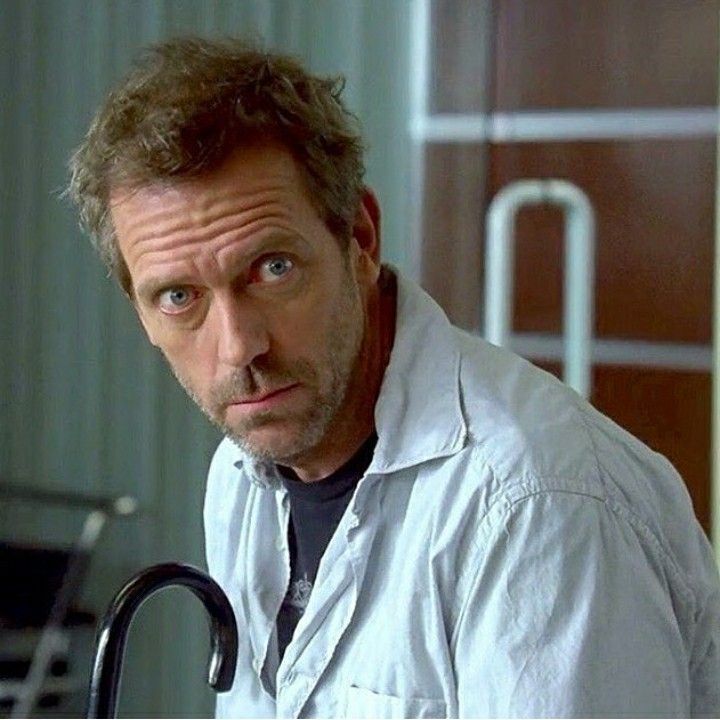

Dr. Gregory House (Hugh Laurie)

House, M.D. which was based on “Sherlock Holmes” has a main character who is both brilliant, self-destructive, and obnoxious. This in large part due to his father who emotionally (and physically?) brutalized him. There’s an episode where the father dies and House has to be anesthetized by his Watson character, Wilson, to be taken to the funeral. We gain tremendous insight into how House was shaped as that part of his life is revealed.

Significant Others

Bonnie loved Clyde. Etta Place, a school teacher, loved the Sundance Kid. Carmella Soprano stood by Tony. Long suffering Abby Donovan put up with anything Ray did – or didn’t do.

Abby Donovan (Paula Malcomson)

Spouses can change or view of our characters by loving and supporting them. We may not understand the relationship fully but we think there must be something about these characters that allows them to be loved.

Tangential to this is a character’s kids. No one doubted how much Ray Donovan loved his children or how Maleficent came to cherish Aurora.

A Moral Code

Most of the characters we’ve met who are challenging also have a moral code that guides their behavior and sets limits on how bad they are.

As mentioned, Dexter can only kill bad people. Tony Soprano has a strict set of rules that deal with how he treats other gangsters. Ray Donovan almost always warns people he’s about to light up. House regularly tells everyone he’s not a nice person and they should avoid him even if he can save their lives.

In Hell or High Water the outlaw brothers have intense loyalty to each other and a plan to rob a dozen banks. Killing anyone during the commission of these robberies is strictly avoided. They just want money. Of course this goes wrong, people are killed, and the film intensifies.